Earn it yourself

Pavel Šulc

soccer

Whenever clips from our match at Sparta in February 2022 pop up on my TikTok feed, I think the same thing people watching on TV probably thought back then: “Damn, what was I doing…”

In the first chance, when Pavel Bucha sent me a curling ball from the wing and I found myself alone in front of the goalkeeper, Holec, I just wanted to shoot in the other directon than he was moving. You’ve also got to acknowledge that he saved it well — it was a fantastic stop. It happens.

But then the ball got cleared, Lukáš Kalvach fought for it again at midfield and passed it to me on the right as I was sprinting forward. I was basically going alone and saw that Kalvy was running down the other side. He was running and yelling for the ball back. Alright then, I’ll pass it to him into the open net…

But I made the pass too long it!

The moment the ball left my boot, I knew it was just out of Kalvy’s reach. “No, man!” flashed through my mind. “Please get to it. Please. Please!”

He didn’t make it.

But at least we still had the ball. Bogy – Jean-David Beaugel – took a shot, and his deflected strike hit me in the stomach. “I’ve just got to finish this. It has to be a rocket,” I was screaming at myself inside. But then all I see is me shooting it straight into Holec’s leg — and everything’s ruined.

The guys are holding their heads. I’m holding my head. None of us can believe how badly I messed that up.

It all happened so fast. I’d been subbed on for the last ten minutes, and we were leading 2–1 at Letná, Sparta Praha home stadium. After missing those clear chances right near the end of regular time, I was praying we’d at least hold on. But then, in stoppage time, Sparta had a corner, Adam Hložek headed it in and boom — 2:2.

I felt horrible. As soon as the final whistle blew, I ran straight to the dressing room so I wouldn’t have to talk to anyone. And right away, I knew this wasn’t just a regular missed chance.

This was bad. This would stick with me.

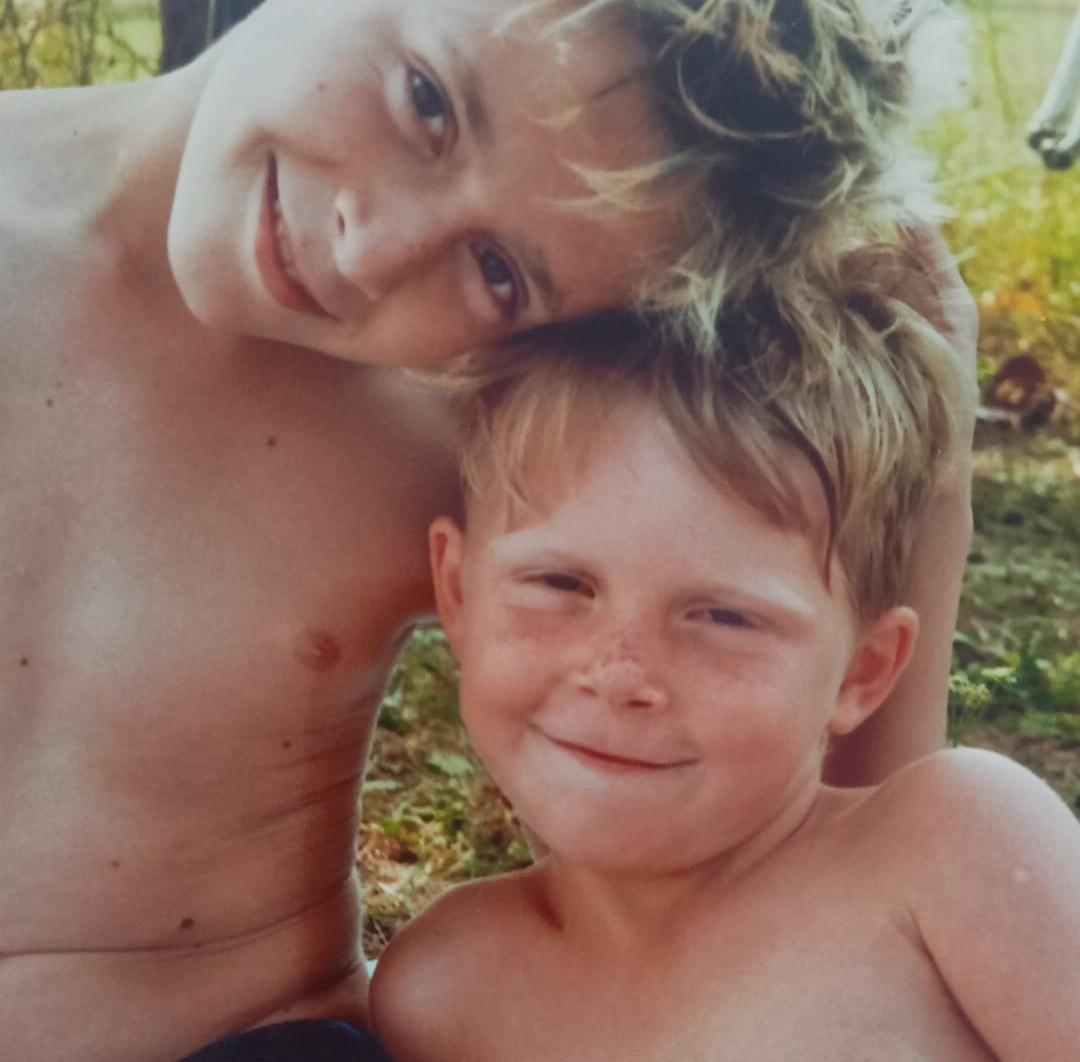

That summer I was seven, and my grandma and grandpa took me and my brother—who’s seven years older—on a trip to the sea in Croatia. After we got back, he got sick. It seemed like a typical case of strep throat. I remember the day I went outside to play with friends and looked in on him through the living room window, where he was lying down so he wouldn’t infect me.

But when I came home, I was told Patty was in the hospital.

What? I didn’t understand. Why?

Apparently, he had woken up and couldn’t move. Ugh… Whenever I think about it, I get chills just imagining how he must’ve felt when it happened.

The worst part was that no one could figure out what was actually wrong with him for a long time. And as a little kid, they didn’t really know how to explain it to me. How could they make me understand that my big brother—who I always goofed around and played sports with, despite the age gap—had suddenly become just a body lying still?

The worst part was that no one could figure out what was actually wrong with him for a long time. And as a little kid, they didn’t really know how to explain it to me. How could they make me understand that my big brother—who I always goofed around and played sports with, despite the age gap—had suddenly become just a body lying still?

Around that time, I started crying for no reason. I just felt sad thinking about how he must be doing. I wanted to be with him. To play with him like I always had since I was little. Not to be scared we might never see each other again.

I share this story—what happened to him and how it deeply affected me as a kid—for one simple reason: when someone asks me today who my role model is, I don’t hesitate to answer. It’s not some big-name footballer.

It’s my brother.

Because of Covid, only a thousand spectators were allowed in the stands at Sparta that time. That’s why my parents were watching the match at home on TV.

When I missed all those huge chances, my dad apparently started yelling around the apartment that it was all screwed. And when Sparta equalized, he turned it off right away. He couldn’t watch anymore.

Because he knew very well this wasn’t the first time.

I returned to Plzeň in the winter after my 20th birthday, following loan spells in Opava and Budějovice, where I had already played top-flight football as a young player — which was great. But Plzeň wasn’t in a good place at the time. Under coach Guľa, we had amazing training sessions and great video prep, but we couldn’t translate any of it into results on the pitch. It just wasn’t working.

It was during that period that I started getting regular minutes, often even starting. One match I especially remember from those early games was in Karviná. We were favorites, but it ended 1–1, and I had two clear chances from Ba Loua’s passes. The goalkeeper made amazing saves both times — I don’t hesitate to call them miraculous.

Still, it kind of stuck with me from then on.

At the start of the next season, I missed three huge chances against Slovácko. One time a defender stole it from me at the last second, then I tried to nutmeg goalie one-on-one. I believed in myself, but I didn’t place it well. And then, in front of an open goal, I just stuck my foot out — the ball hit my ankle and went flying over. It happens. But even that match, and my missed sitters, got picked apart on famous TV show. That pissed me off. I kept replaying everything in my head, thinking what I could’ve done differently — but at least we won that one.

And the season had actually started well. I helped in the Conference League qualifiers — I started and scored against Brest. But after we got knocked out in extra time by Sofia, it felt like everything started to fall apart. I lost my form, I wasn’t playing like I know I can, and I stopped scoring. In a 0–1 loss to Hradec, I got subbed off at halftime. From then on, I only came on as a sub. And since we were only playing the home league, there weren’t many chances to get into rhythm. The coach had no reason to change the lineup when the team was doing well.

And then Sparta happened. The final nail in the coffin of my confidence.

Even on my way to the locker room, I knew exactly what this would trigger. The fact that we lost the win at the very end against a direct title rival — and that it was on my foot… three times on my foot — of course people were going to talk about it.

The guys on the team were pissed at me — there’s no better way to put it. No one openly yelled at me, but just from their looks and how they acted, I got the message. Even the coach didn’t really back me up at the press conference. He said something along the lines of how we lost the win because of my missed chances. I get it — he was emotional too, and there’s no point dwelling on it years later. But I can’t say I felt any real support from him back then.

At least our backup goalkeeper Aleš Hruška came to me right there in the locker room. One of the oldest guys on the team. In moments like that, no words really help — I knew myself I had screwed it up. I was angry at myself. But Aleš still helped. Not just that moment, but overall — he acted like a shield for me with the older players. Even that night, he texted me, telling me to switch everything off, not to read anything, and not to give up. That it would turn around.

I sit near the front of the bus, so I just sank into my seat and didn’t look left or right. Even the silence of people walking past me cut deep. And then, during the ride, I heard them talking about it. That’s nothing unusual — we always analyze plays on the way back from matches, both the good and the bad. But at that moment, I just didn’t want to hear it again and again. And besides — this time, it was different. I could feel I had really let the guys down.

So I cried. I cried the whole way from Prague to Plzeň.

I couldn’t get those chances out of my head. Why? Why didn’t I shoot better? Why didn’t I pass a little further back...

Our physio Michal Rukavička sat with me for a while. He tried to lift me up. It was a nice gesture, but in a moment like that, those are just empty words. He and I both knew that nothing could change the reality. And that was clear: I let the team down.

My mom called, wanting to know how her little boy was doing. She didn’t want me to be sad. She’s a gem.

At the same time, when I picked up my phone, there were already like five hundred messages on Instagram. Insults, death threats, and other crap. People seem to think we screw up on purpose out there. It was awful. And then came the Sparta fans making fun of me. I actually laughed at that one — they were so desperate at the time that my failure gave them something to cheer about.

I looked at a few of those messages, but there was no point reading them. I deleted everything right away, didn’t even open the rest.

And even then I was already telling myself:

“Just wait, you ****. I’ll show you.”

It’s called Guillain–Barré syndrome. You can easily look up the exact definition, but what I know is that it’s a disease that attacks the peripheral nervous system. As if it shuts off all the nerves that control the movement of different parts of the body.

That’s what my brother was diagnosed with after a series of tests.

The only way to overcome the illness is through exercise. Endless exercise, where you start by simply trying to think about the most basic movements, so the neural pathways can slowly rebuild. It’s a daily, unimaginably exhausting grind, where after a month of effort you might move your finger a few millimeters.

That’s exactly what my brother had to go through. Nurses would move his arms, legs, fingers — every day. But his incredible willpower and determination to get better eventually paid off. And so did the strength of our family — because Mom spent three years with Patty in the hospital in Prague, while dad and I tried to keep things running somewhat normally back home in Toužim, 80 miles away.

That’s exactly what my brother had to go through. Nurses would move his arms, legs, fingers — every day. But his incredible willpower and determination to get better eventually paid off. And so did the strength of our family — because Mom spent three years with Patty in the hospital in Prague, while dad and I tried to keep things running somewhat normally back home in Toužim, 80 miles away.

We wrote letters to my brother and mom, and whenever football allowed, we visited them on weekends. I often secretly spent the night in their room. It wasn’t allowed, of course, but for mom and me, it was the only time we could really be together during that period.

And later, when my brother moved to a rehab center, he would sometimes stay in a hotel with dad over the weekend, while I stayed at the spa with mom. No one really needed to know about that either.

The most important thing is: my brother gradually recovered from what was originally a terrifying condition. At least enough to live a normal life — though his feet still don’t work quite right. He wears special orthotics in his shoes and uses a cane like Dr. House.

When he and mom finally came home, it was right around the time I had to start commuting to Plzeň for my football development. I was so excited for that — but at the same time, I hated every moment of leaving the house, because I just wanted to be with them.

It was a strange period. A weird mix of excitement that I had a shot at playing for a freshly crowned champion club, and emptiness because, after all that time waiting for two of my closest people to come home, I was the one leaving them again.

As soon as we got to the stadium, I jumped off the bus, threw my stuff in the locker room, didn’t say a word to anyone, got in my car, and drove home.

I wasn’t feeling well. What happened at Sparta just underlined how I was feeling in the dressing room at the time.

I was twenty, the youngest in the squad, where the older guys stuck together. They had built a solid core over the years, and I was the only young one inserted into it.

That alone isn’t unusual — anyone who’s ever played a team sport at any level knows how that works. If you’ve got a tight-knit group of friends and someone new comes in who doesn’t quite fit in right away, it’s not ideal for either side.

And I didn’t fit in — let’s be honest. Actually, I wouldn’t be surprised if I annoyed the older guys a bit.

And I didn’t fit in — let’s be honest. Actually, I wouldn’t be surprised if I annoyed the older guys a bit.

It’s also part of my nature and the way I sometimes look — I know people often think I’m judging them or that I don’t respect them. But I know that’s not true. That’s not how I see it. I just like doing my own thing and not having to adjust to others too much. That’s true, too.

Either way, when a young player joins a team with strong bonds, basically takes someone’s spot, brings a certain energy, and then botches a few massive chances that cost the team points — it’s no wonder he’s not going to be the most loved.

And I understood that. I just kept thinking: “You don’t all have to like me, fine — but I’m trying to help you. And if I’m playing, then the coach must think I’m capable…”

The worst part was that I really was alone. I had no one to lean on. Later, when guys like Panoš, Kabongo, Paluska, or Sojka started at Viktorka, at least they had each other. I had no one my age around me.

Funny thing is, we ended up winning the title that season — and only four players appeared in more league matches than I did. From that perspective, it was actually amazing, the best thing that could’ve happened to me.

But…

My feelings at the time were different. Especially after that disastrous Sparta match, where dropping two points against a direct title rival made things a lot harder.

The following week, I was really off. I couldn’t shake the bad mood. I wasn’t myself — not in confidence, not in how I played. I couldn’t stop replaying how I screwed up at Letná. It didn’t help that I didn’t play at all in the next game and, in the remaining matches, only came on for a few minutes at the end.

But once the worst of it passed, I made a decision: no more self-pity. I was going to flip my mindset completely.

Alright then. So what? I’m not playing, not even with the B-team, which means I’ve got loads of unused energy. I’ll pour that into improving my skills. So every morning at 7, I was already at the stadium, got changed, took a ball, and started kicking it against the wall, working on my first touch.

I won’t claim I kept that up forever. Once I got back into the starting lineup the next season, I appreciated getting that extra hour of sleep again. But even then, I kept the habit of staying after training for ten extra shots from the penalty spot — just to feed my brain the feeling of hitting the target, scoring over and over again. The subconscious really works wonders that way, seriously.

So yeah, in a way, Sparta was a turning point for me. That’s when I started regularly doing extra work. Because I really believe in this simple equation: anything extra you put in, will come back to you on the pitch. Somehow. Not always in a measurable way, but that effort adds up somewhere.

I always think of that when I play a great match — I feel amazing, everything clicks — but I end with zero goals and assists, and we lose. Even then I know I gave it my all, didn’t slack off. And sometimes it’s the other way around — I can’t find my rhythm, the ball’s bouncing away from me, and suddenly a lucky rebound lands right in front of an empty goal and I score.

I take moments like that as a reward for everything I’ve put in when there was no visible payoff.

What kept me afloat after Sparta was my family. I honestly don’t know if I could’ve handled it without them — without my girlfriend and even our cat, who always manages to calm me down.

When I got the award for best league player in the 2024/2025 season, I said it was a prize for my whole family. And I meant it. My parents have always been there to support me. And Natali — my girlfriend, who I’ve been with since I was sixteen — has been with me every step of the way these past few years. I often tell her that everything good that’s happening to me is thanks to her. She’s amazing. She doesn’t stress me out with nonsense, lets me unwind, doesn’t nag if I just want to play some video games. She’s exactly the kind of person I need by my side.

She has her own career, works, studied dental hygiene, and is continuing her education. Even her family — none of whom cared about football before — now follow all my matches closely. They all share the highs and lows with me.

Natali also came up with my look. The glasses and headphones I wear in public — that was her idea. She said I should create a signature style to help get into game mode. I went with it.

I’ve never felt the need to hire a mental coach — Natali is more than enough. She’s trained me plenty.

She’s not the kind who just says, “It’s going to be okay.” Even back then after Sparta, she didn’t coddle me.

“Well, so what? Then you’ll just have to start working harder,” she told me.

Sure, sometimes you just need a hug and to hear that everything’s going to be fine. But there wasn’t space for that anymore, and Natali read that moment perfectly.

“Order some Adidas balls and a pair of boots for me, and we’ll go kick around together,” she offered.

I actually ordered them. Even though she only wore them once at home, it was a great gesture.

And my dad… He played football himself and coached me when I was little. He’s a football fanatic — he’ll watch two matches at once, one on TV, one on the computer. We’re always analyzing games together, talking about specific situations. But he’s also level-headed. He tells me that at this level, he has nothing left to teach me. He just tells me how he saw things. And he often reminds me to stay calm and keep working. That’s the only way to move forward. He said the same thing after the Sparta game.

My mom and dad even used to drive across the whole country to visit me in Opava. I still can’t believe that. And since the very beginning, Natali has barely missed a match.

Same with my brother.

Vstoupit do Klubu

Inspirativní příběhy vyprávěné sportovními osobnostmi. Ke čtení nebo v audiu namluvené špičkovými herci. K tomu rozhovorový podcast. Každý týden něco nového.

Did you like the story? Please share it.