Simple lucky gal

Carla MacLeod

ice hockey

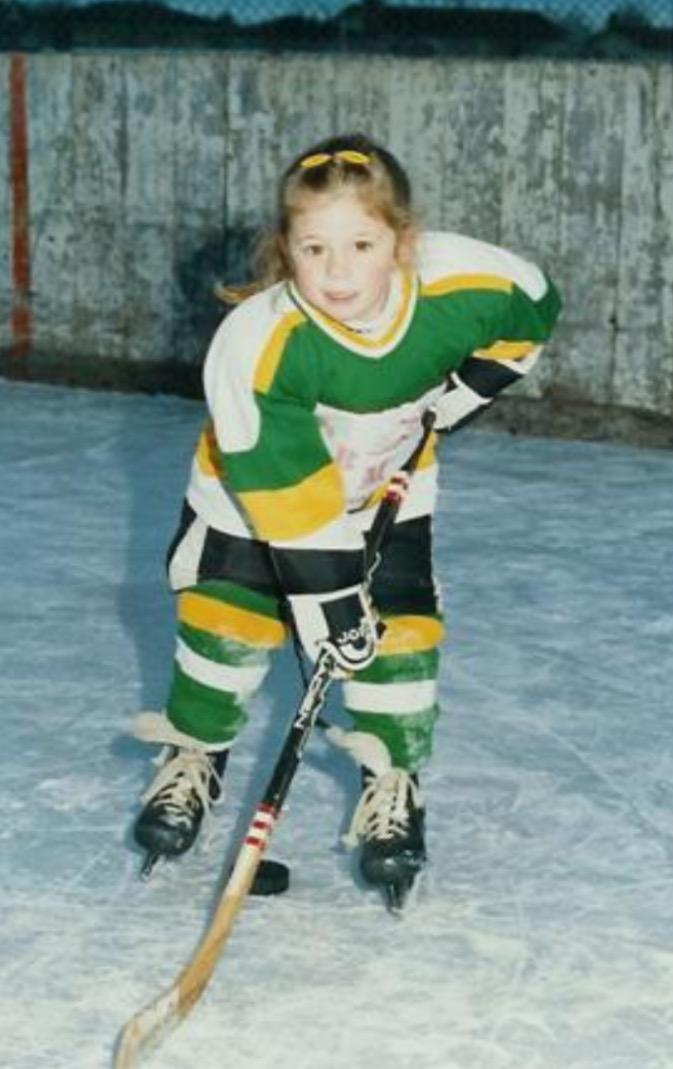

Forward, wing, left-handed shot. Good skating, dangerous wrist shot. Blonde.

Va-ni-so-va.

OK, next.

Forward, center, left-handed…

I was sitting on the beach of Maui, glancing at the ocean and scrolling through cards with photos and basic facts about the players, who I was about to meet at our first camp in a few days.

Tej-ra-lo-va.

A year before, I mentioned at the World Championships in Calgary among friends that if I ever were to coach internationally, I would want it to be Czechia. I really liked the way this team plays—its style, emotion, and overall game. It genuinely excited me.

And suddenly, here I am. I am the coach of the Czech national team. The next championship is approaching, and on my vacation I'm sorting through the names, matching them to faces that will soon look at me with expectations, hoping I'll help them achieve their goals.

Going to another country, you simply don't know anyone. No one. At first, everyone looks the same, names are hard to pronounce. From my earlier experience in Japan, where everything happened very quickly, I remembered the feeling of needing to orient myself fast but having nothing to hold on to.

I was going to be prepared; I had done my homework. I wanted to show them I really cared.

Because when you show you care, others are more willing to trust your vision. It's not just about saying: "Here I am!"

Beforehand, I connected with each player one-on-one to talk, to get a sense of who they are not just as players but as people. I took notes and then compiled them into those cards I was studying intensely.

But what I couldn't prepare for were doubts—about myself, my work, my approach, what I was really trying to achieve, and whether it was worth trying at all.

But we'll get to that. First, you probably want to know where this Canadian girl came from and how she ended up on the bench of the Czech hockey team. So, let's start from the beginning…

“Go after her! Get that girl!”

How many times did I hear that as a child. Mostly from the parents of my opponents. On small rinks, their shouting echoed beautifully.

As soon as the rules allowed body checking, I started tucking my long hair under my neck guard. They still knew I was there somewhere, but in the rush of the game they at least couldn’t immediately recognize that the player in the battle was me.

Because I played with boys my age from early on, I had to be smarter. I just had to figure things out differently not just using my strength.

Even so, I sometimes took some really dirty hits. But that led to wonderful reactions from my teammates, who immediately rushed to defend me. With all my teams, every group I ever joined, I had perfect relationships.

There’s this great story that captures it: some parent of one of my teammates didn’t like that I was in the locker room with the boys. Of course, nothing happened between us, we were just a hockey team. We had it organized so that the boys changed first, and then I came in. There was no problem. Yet this question appeared. It was beautifully resolved: everyone stood firmly behind me, and it ended with the boy whose family complained changing on the side. I stayed in the locker room.

There’s this great story that captures it: some parent of one of my teammates didn’t like that I was in the locker room with the boys. Of course, nothing happened between us, we were just a hockey team. We had it organized so that the boys changed first, and then I came in. There was no problem. Yet this question appeared. It was beautifully resolved: everyone stood firmly behind me, and it ended with the boy whose family complained changing on the side. I stayed in the locker room.

I think in 99% of cases, the girl would have been moved aside, but here they stood up in a unique way.

I was lucky because from the very beginning in hockey I encountered coaches and other people around teams who treated me wonderfully and helped me. Back then, in the late 1980s, even in Canada it wasn’t common for girls to be on teams. I’m not saying girls didn’t play elsewhere, but I personally met about one per season in childhood. I’m not sure, but I’m almost certain that in my league I was the very first registered female player. And when girls played elsewhere, from what I heard, they were not always treated quite right. But I was fortunate to have good people who invested energy in me without hope that it would lead to anything hockey-related. Back then, there was no women's league, no clear hockey future for me. But my coaches didn’t care about any of that—I was simply their player. They even protected me from outside noise, like questions about why that girl was there, taking spots from boys.

When I hear stories from my Czech players about how they had to grow up in boys’ groups, pretend to be one of them, or change their names, it doesn’t surprise me. It looked pretty much the same in my childhood. It may not seem like it, but we have a lot in common. Canada may be ahead but only by one or two generations.

But as a child, I didn’t think about anything like this. I just played. I just accepted that things were a certain way and did my best to live my passion for hockey. Because I loved it so much! I remember how I couldn’t wait to come home from school, put on my rollerblades, and start shooting pucks. I did that for hours and hours. Nobody told me I had to or should do it to improve—I did it on my own because I enjoyed it.

But as a child, I didn’t think about anything like this. I just played. I just accepted that things were a certain way and did my best to live my passion for hockey. Because I loved it so much! I remember how I couldn’t wait to come home from school, put on my rollerblades, and start shooting pucks. I did that for hours and hours. Nobody told me I had to or should do it to improve—I did it on my own because I enjoyed it.

And I had one dream, though unrealistic: that one day I would play for the Oilers.

Growing up in the 1980s Edmonton suburbs, the Oilers meant everything. We knew them all: Messier, Fuhr, Anderson, Coffey… We had the chance to meet many of them live at community events. On my bedroom wall hung a Wayne Gretzky poster, and I dreamed of being like him.

I don’t remember which specific game it was, but the awe I felt when I first entered the Northlands Coliseum still stays with me. To enter the scenery I knew from TV… Everything seems so huge when you’re a kid. And seeing your idols in person makes you feel more connected to them. Later, as a teenager, thanks to my dad’s job in Calgary, I got to go to a Flames game against Los Angeles, where Gretzky had been traded. How I loved him! I watched every move as he skated just outside the blue line, believing that one day I would skate in front of crowd like this just like him.

It was 2015. I was driving home from work and called my parents. Just to chat about how special it was that I had just been inducted into the Alberta Sports Hall of Fame.

My parents said something that perfectly captured my feelings: “Carla, when you were little, we didn’t even realize you were any good.”

It’s true. I didn’t even see myself that way. Never during all those years did it cross my mind that I might be an exceptional player. I simply ran around the street with a hockey stick with other kids, and my coaches let me play on their teams. I understood I was playing at some level, maybe getting to a higher one, but I never thought I stood out in any way.

I’m really just an ordinary gal who had tremendous luck in life.

For example, just being able to grow up in a family with a strong and loving background. The security my parents gave me and my three siblings allowed us to just be kids and not worry about anything else. They encouraged us to follow our dreams and were always supportive. They valued honesty and worked hard in life. We didn’t have bells and whistles that some other families around us did, but we had plenty of love at home. We still do.

The older you get, the more you realize how special is that. I was incredibly lucky to have the parents I do. Just the fact that in 1986, when I asked them if I could play hockey, they said yes was exceptional. Because they didn’t have to say yes.

Girls simply didn’t play hockey back then.

I remember so many situations when someone didn’t believe me or tried to discourage me, but I could always go back to my parents and they supported me. Always. At the same time, they let us kids solve whatever we needed to solve ourselves. They didn’t do things for us. They just encouraged us to fight for whatever it was. They were there for us. They believed in us but also let us fail, learn from mistakes.

And they didn’t put expectations on us that we had to achieve certain things.

They didn’t put me into hockey with the expectation that I had to be a great hockey player one day. They let me figure out what I could and couldn’t manage. They never worried about the results. They just made sure we had the chance to pursue what interested us. I laugh when I think about all our ideas… hockey was definitely the best one.

Before we moved to Calgary, I grew up in Spruce Grove, a cul-de-sac neighbourhood. Many kids of similar age lived around, so we just kept playing all the time. Riding bikes, climbing trees, fooling around on trampolines, skiing… but mostly playing hockey. Especially in Alberta at a time when Edmonton and Calgary were winning Stanley Cups, it was everywhere. We played on the street, on ponds. Anywhere.

In one article, they once dug up that my great-great-grandmother on my dad’s side was sister to the grandmother of Maurice Richard, one of the most famous hockey players in history, after whom the NHL’s top scorer trophy is named. Great—I’d take his skills, especially to learn to shoot better, but this fact was never even mentioned in our family during my childhood. Besides, in Canada, almost everyone has someone in their extended family who played professional hockey. Because basically everyone plays it there.

But in my passion for hockey, none of that mattered. What attracted me was the environment itself. My siblings. Neighborhood kids. I don’t even remember when I first picked up a hockey stick, but there are photos of me at two years old wearing my older brother’s gear. I apparently started skating at two and a half.

As far back as my memory goes, hockey was a solid part of my life. My love for it never faded; in fact, it only grew.

The event is called the Canada Winter Games, a kind of small national Olympics for talented kids. It was held at the end of winter 1995, the last year I played boys' hockey. I was selected for the Alberta girls' team, where most teammates were around seventeen or eighteen years old.

I arrived among them as a twelve-year-old seventh grader.

That time, I also got news that women's hockey would debut at the 1998 Olympic Games. Just that information thrilled me.

I was already starting to suspect that I might not play for the Oilers after all, but suddenly I had a different dream. A more realistic one. When I returned home, I started practicing my autograph and drew Olympic rings everywhere.

Of course, still only in a childish version, but I had already begun thinking about everything fulfilling that goal would entail. And I didn’t have to think long because one of my coaches at the time, Kathy Berg from Calgary, was behind the Olympic Oval program, aimed at gathering the most promising female hockey players from western Canada and centralizing them in a training center. So that systematic work on advancing women's hockey could begin.

Kathy asked my parents if I could participate in the program too. And they said, "Sure."

Because they trusted Kathy. And because they trusted me.

The program included players like Hayley Wickenheiser, Dana Antal, and Kelly Bechard—all future successful Olympians—and all about five or six years older than me.

At twelve, I started training with them. I didn’t think about what it meant for my life; I just wanted to be a hockey player, and this was my chance to truly become one. I simply took advantage of being put in an environment that was supposed to allow it. And my parents let me.

That doesn’t mean I wasn’t nervous. I was. And how!

Not that I ever wanted to go back home or give up such an opportunity, but during on-ice drills, I counted for myself how far down the line Hayley was so I wouldn’t have to pair with her. Because she was on a totally different level. Later, we became teammates and shared many experiences, but back then, as a little girl, I was genuinely afraid of her.

My transition into women's hockey was unique because this program pulled me into the top level at such a young age. I trained and played with these girls on a newly formed Calgary team.

I loved playing with boys, and to this day, I have my best friends among them, but my hockey got a whole new dynamic here. The game was different. With boys, we were all roughly equal, but here I suddenly belonged to the best, and I had to learn to deal and deliver what was expected of me. That taught me to express myself on the ice and think differently than I was used to.

I stayed in the Olympic Oval training group during my university years, which gave me the best of both worlds. I played on the team where I learned to be a leader, and with the best in the country, I could train regularly, which improved me.

Most importantly: once I entered the national program, a clear path to fulfilling my dream lay ahead. I knew it would take a lot of work, but I also knew that if I gave my best, I had a chance.

I was on the radar.

Vstoupit do Klubu

Inspirativní příběhy vyprávěné sportovními osobnostmi. Ke čtení nebo v audiu namluvené špičkovými herci. K tomu rozhovorový podcast. Každý týden něco nového.

Did you like the story? Please share it.