Just shoot it

Patrik Berger

soccer

The penalty shot was horrendous.

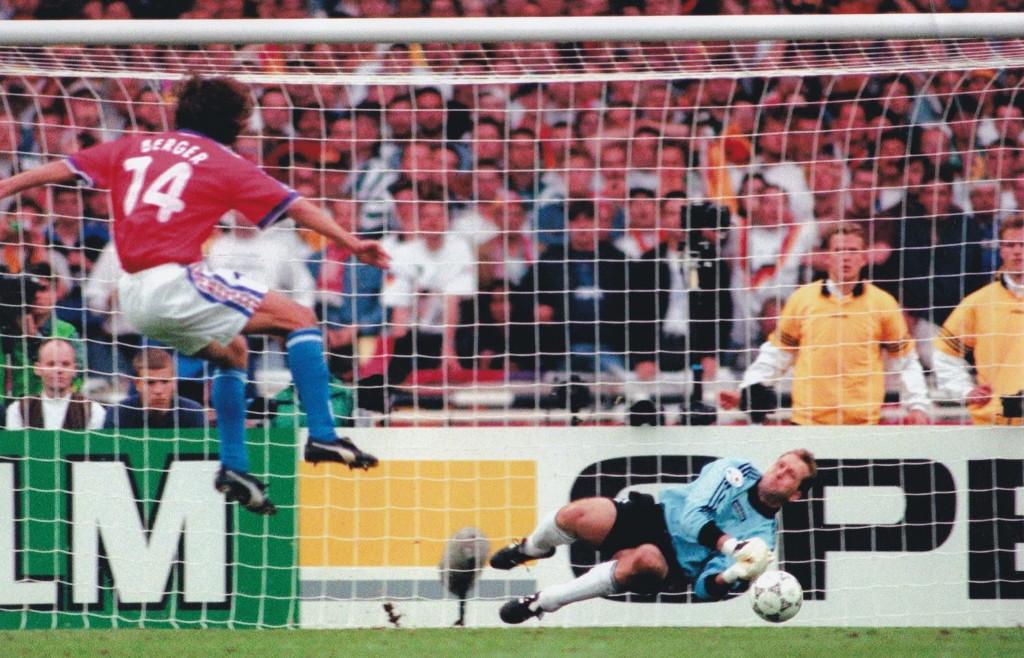

Andreas Köpke, the German goalie, jumped to his right but somehow, the ball slid right under him. I guess I was lucky that I kept it low. A goal is a goal, right? I still felt terrible.

There were two players designated for penalty kicks in the finals of Euro 1996. Pavel Kuka and I. Just as the referee signaled a penalty shot after a foul on Karel Poborský, my eyes turned to Kuka. There was fear in them.

“Fine, I’ll do it,” I thought, but I was nervous as well. Honestly, I probably wouldn’t want to be in that situation ever again, but I was so focused that it took me years to notice on a video that a German player had tried to throw me off by distracting me. I didn’t care about him. I didn’t care about anything at that moment. I was just repeating to myself, “Don’t try anything overly complicated. Just shoot it.”

When the ball went in and we had the lead, I breathed a sigh of relief. I fell to my knees and spread out my arms. Then the rest of the team covered me.

I actually still have the cleats from that game at home. All it takes to remember that game is to close my eyes and let the memories flow. We were total outsiders. No one even expected us to get out of the group stage. And we lost our first match, 2-0 against Germany. They crushed us, just as expected. Italy and Russia were ahead of us.

Our second loss didn’t come until the final. The golden-goal rule got us. We lost to Germany in overtime, 2-1. It was the only time in history this rule was used, but we never expected to get that far. Vladimír Šmicer had a wedding planned the week after the semifinals. He went to Prague one day in the morning, enjoyed the euphoria from the ceremony in front of the full Old Town Square, and he was back in London that night. The management didn’t let him stay for the wedding night. You should’ve heard the jokes we shot at him, but he wasn’t the only one with plans. A lot of teammates had holidays booked for the final stages of the tournament and they had to cancel them.

Even the beer we had from Radegast, our sponsor, was only enough for the three group matches. Our mascot, Pivrnec, was sitting at the tap and we took him everywhere with us. It was just that he didn’t have anything to offer us after the group stage. So every time we’d advance, we’d celebrate with that English non-beer. It was good enough, though. I mean, we were preparing for the final game of Euros. The first one for us in 20 years. It sucked that we lost it. No one was in a party mood that night, but looking back, that silver felt like gold for us.

To illustrate how few expected us to advance beyond the group stage, I remember this question from my teammate from Dortmund, Jürgen Kohler; one of the best defenders of his time. During our last practice of the club season, he asked me at warm-up, “What are your plans for summer?”

“I’m going to Euro,” I said.

“You’ve got your tickets? Gonna watch some games, yeah?” he asked, dead serious. He had no idea the Czechs had qualified and that I was playing with the national team.

“What do you mean?” I said. “We’re going, and we’re going to win!”

He just laughed.

And we were that close…

I had already played for one year in Germany, but for others, that Euro was a door opener. Pavel Nedvěd went to Italy, Karel Poborský to England, Vladimír Šmicer to France, Radek Bejbl to Spain. All of them were in their early 20s; all of them at the start of their careers. It shows how well structured a team we had. The young and tireless fit in well with the experienced ones. We had huge respect for our opponents at first, because of all of those famous names, but then we realized that we could play with anyone, that we could defeat anyone in just one game.

Thanks to our incredible team spirit, we were able to enjoy another cheerful evening. And then another. And another.

We lived in Preston, in a two-story hotel we had to ourselves. Downstairs was a big room where we had food and there was also a bar. We gathered there after advancing from the group stage.

Then after the quarters.

Then after the semis.

We went to bed later than sooner. I remember how our coach, Uhrin, together with Ivo Viktor, the goalkeepers’ coach, would leave to go to bed, acting as if they couldn’t see us. No one cared that we stayed up until the morning. That’s how euphoric we were.

After the finals, we were sitting in London, tired, disappointed before heading home the next day. For many boys, this was the start of amazing years with the national team. For me, it was my last big joy in the national jersey. For different reasons, it wasn’t that fun for me afterward.

First, I didn’t want to play under Uhrin because of what he did at the training camp before Euro 1996. He said that he had not yet decided whether he wanted me or Martin Frýdek; that we both would get our chance in the next two friendly matches and he would decide after them.

I thought that was fair. But except for a few minutes on the field as a substitute, I stepped on the field for the first time at Euro, in the second half with Germans when we were down 2-0.

I couldn’t trust him anymore because he wasn’t honest with me. I even wanted to go home from England; had my things packed. We had been sleeping in double rooms in Preston and between each bedroom was a door. Šmicer stood in our doorway and watched me pack my last bag.

“What are you doing?” he asked. “Stop messing around.”

But I didn’t care. My manager, Mr. Paska, was the one who made me stay, but my bag was only unpacked halfway as a little, silent protest. Lucky me.

Anyway, I didn’t want to play under Uhrin after the tournament ended. It’s over now, all forgotten and we’ve seen each other numerous times now. But at that time, I was pissed. There were times when I regretted not continuing with that amazing team, but it was stronger than me.

I returned to the national team once Josef Chovanec took over. I was just a spare at our first camp, but someone got injured before the first qualification match at the Faroe Islands so they called me. I couldn’t wait to be back with the boys.

That game was easy to remember. We played in such thick fog that one couldn’t see from the net to the corner flags. I got on the field for the last 20 minutes, passed it to Šmicer for a goal, and we won 1-0. We had qualified again. Everyone gained some experience and we played good soccer together. It was fun. The tournament itself, Euro 2000, ended terribly though. I couldn’t play in the first two games so I only played in the last group game against Denmark.

And that game was just for fun after the first two.

Vstoupit do Klubu

Inspirativní příběhy vyprávěné sportovními osobnostmi. Ke čtení nebo v audiu namluvené špičkovými herci. K tomu rozhovorový podcast. Každý týden něco nového.

Did you like the story? Please share it.